Page 23 - ENGLISH_FullText

P. 23

One important standard was the size of the accommodation. The

initial standard was set with reference to the cramped conditions of the

old private tenements. Nonetheless, once the standard was laid down,

it became formally institutionalised and efforts to change the standard

became a politically divisive issue, subject to criticisms and reservations

across the board. Numerous protracted bureaucratic meetings were

required to achieve consensus, thus leading to prolonged indecision.

As a result, the standard of accommodation in the PRH sector

changed very slowly and lagged behind developments in the private

market. This gap between the private and public sectors has not narrowed

significantly since.

The government’s public housing policy is therefore the direct

reason why an unreasonably large proportion of housing units in Hong

Kong are too small. Any public housing programme is unavoidably

committed to building uniform-sized units for all. Yet when these units are

small, then a considerable number of them will be occupied by better-

off households who aspire to live in better and larger units, and the public

sector provision has fallen short of this aspirations for the past 60 years.

3.2 The Inequity of Our Housing Policy

Given the large difference in the median size of the housing units

between the private and public housing sectors, an efficient or optimal

housing arrangement would require that there be very different income

levels between the occupants of these sectors.

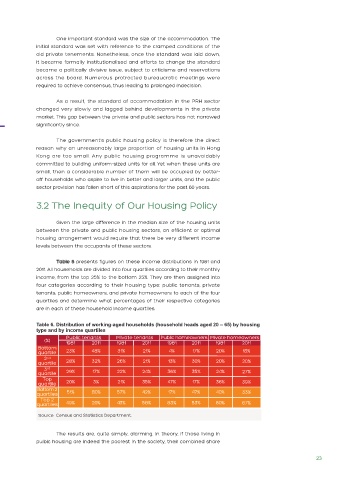

Table 6 presents figures on these income distributions in 1981 and

2011. All households are divided into four quartiles according to their monthly

income, from the top 25% to the bottom 25%. They are then assigned into

four categories according to their housing type: public tenants, private

tenants, public homeowners, and private homeowners to each of the four

quartiles and determine what percentages of their respective categories

are in each of these household income quartiles.

Table 6. Distribution of working-aged households (household heads aged 20 – 65) by housing

type and by income quartiles

Source: Census and Statistics Department.

The results are, quite simply, alarming. In theory, if those living in

pulbic housing are indeed the poorest in the society, their combined share

23